The 2019 UK General Election held on 12th December has been described as a Brexit Election. Boris Johnson called the election with a pledge to “get Brexit done” only months after being elected Conservative leader on the platform of promising to leave the EU on October 31st 2019. But was the 2019 General Election a Brexit election or merely the continuation of long-term realignments in British Politics? We examine the evidence in a new paper, which we summarise in this blog.

The Brexit referendum vote did not occur in a vacuum. The rise of a cultural dimension in political attitudes together with the decline of party identification has created the conditions for electoral realignment. In our recently published book, Electoral Shocks, we argued that Brexit accelerated this process by raising the salience of socio-cultural issues including immigration, and by changing the perceived competence and social imagery of the parties on these issues. But should we think of these shifts in electoral allegiances as a realignment or a temporary blip?

While it may be too early to announce a stable realignment of British politics, we can examine the extent to which the recent electoral change is consistent with what we might expect under realignment. On the face of it, the relationship between Brexit vote and party choice provides telling evidence. Data from the British Election Study Internet Panel shows a steady upward trend in the proportion of Conservative voters who were Leavers and Labour voters who Remainers. By the 2019 election over 80% of both major parties’ support was drawn from their ‘own side’ on Brexit. However, realignment suggests a more fundamental shift in underlying patterns of support. Indicators might include a re-stabilisation of individual level party choice following a period of heightened volatility; substantial shifts in the social and geographical bases of support; and the rise of new political identities based around the new electoral cleavage. Here we briefly provide evidence for each of these.

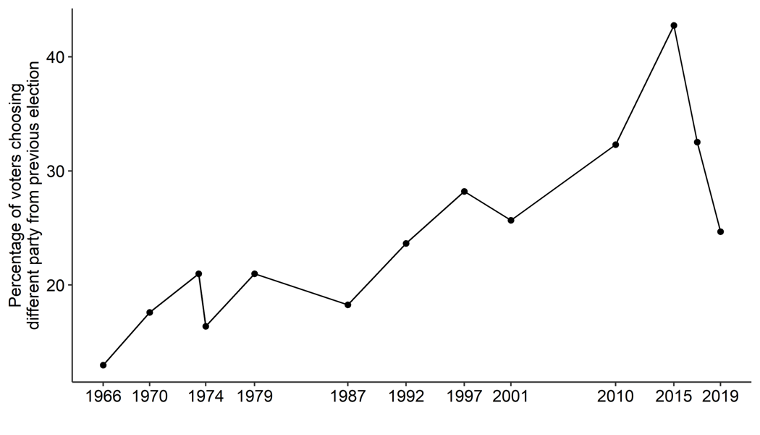

1. Volatility

A drop in volatility could indicate a return to relative stability based on new alignments around Brexit. The 2019 election saw a relatively low level of aggregate volatility, returning to a level seen in most historical elections in the UK. However, more important to our understanding of electoral change, is the amount of individual level vote-switching. Figure 1 shows that there was a substantial decrease in individual level volatility in 2019 compared to the previous two general elections. Following two historically volatile elections, individual level volatility is now at a similar level to that seen in 1997 and 2001. This suggests that support may be settling into a new (relatively) stable pattern.

Fig 1. Individual-level voter volatility in twelve pairs of elections, 1964-2019 [Source, British Election Study]

2. Geography

One of the most remarked upon features of the 2019 General Election results was the collapse of Labour’s ‘red wall’. The loss of previously safe seats in Labour’s working class industrial heartlands – running from North Wales all the way to the North East of England, taking in places held by Labour for decades such as Stoke-on-Trent, Bolsover and Sedgefield – was a vivid symbolic representation of the ongoing realignment around Brexit. The encroachment of the Conservatives in Northern England, while failing to gain ground in the South, marked a significant reversal of the otherwise long-standing North-South divide. Following the Brexit vote, at the 2017 General Election Labour made greater headway in constituencies which voted to remain in the EU. In 2019 it lost support disproportionately in seats that most strongly voted Leave and which were formerly Labour seats. Conversely, the Conservatives strengthened their vote share in Leave areas. History tells us that a changing geographic basis of support can in itself be indicative of realignment.

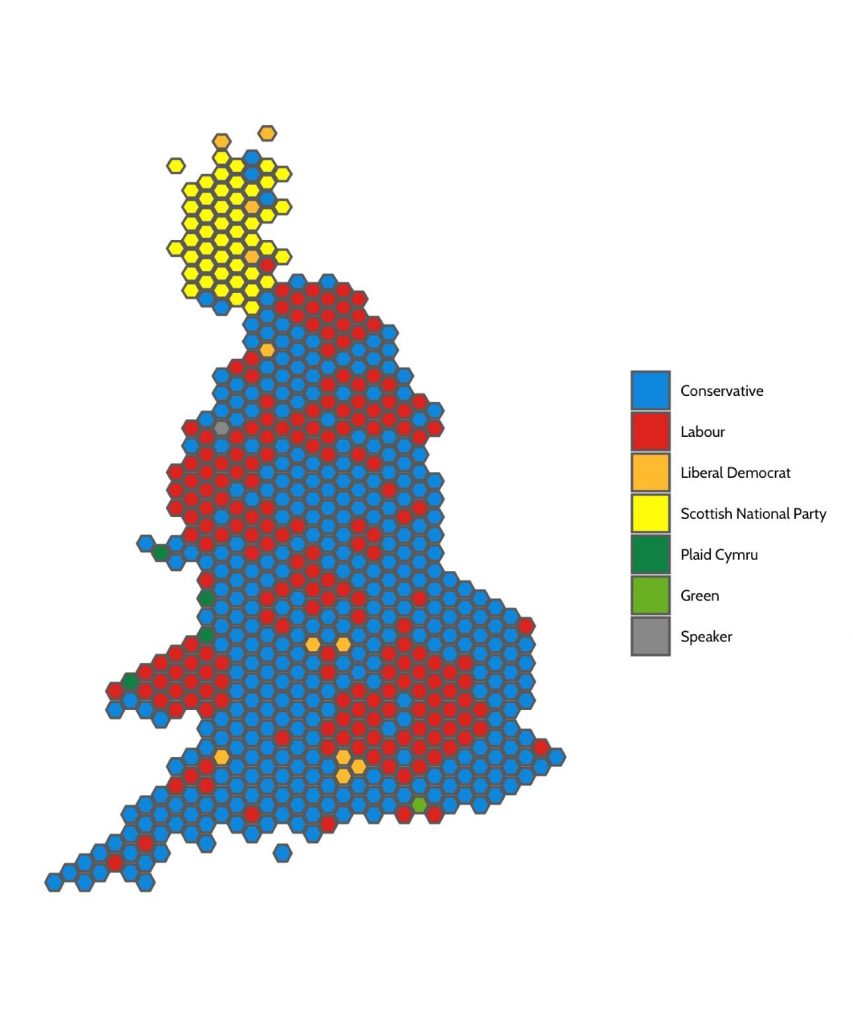

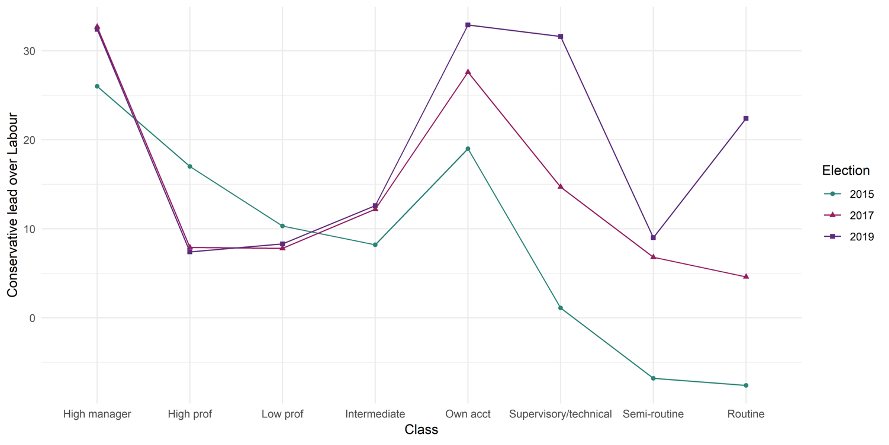

3. Social Class

The fall of Labour’s ‘red-wall’ seats not only represented a Brexit-driven shift in electoral geography but also reflected a continuation of the changing class basis of British electoral politics, and the weakening of Labour’s working class base, especially since 2015 (see Figure 3). Labour’s 2019 losses were much larger among the working class (especially supervisory/technical and routine workers) than the other classes: 18% of working class (routine and semi-routine workers) Labour voters defected to the Conservatives, compared with just 11% of Labour voters overall. This reflects the stronger support for Brexit among the working class (62% voted Leave), compared with the middle class (higher managers & higher/lower professionals) voters (46% voted Leave). The class basis of support in Britain looks increasingly different to what it did in the heyday of class politics.

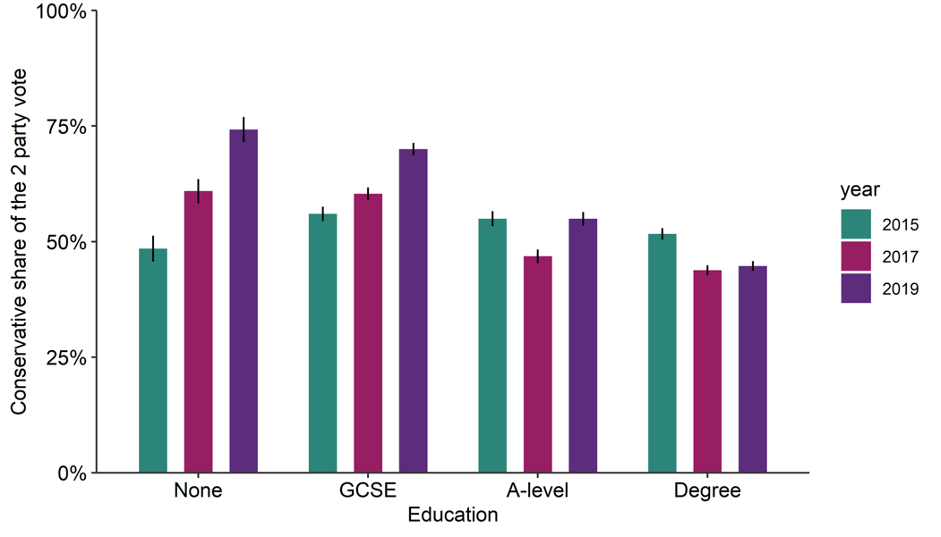

4. Education

The changing social patterns of support in 2019 are not restricted to social class but can be seen in the increasing importance of education as a predictor of vote choice. Education was a very strong predictor of Brexit vote in 2016 and subsequently became an increasingly powerful predictor of party choice. This is apparent when looking at the choices of voters without any qualifications. In 2015, 49% supported the Conservatives among those who voted for either of the major parties. This increased to 61% in 2017 and was 74% by 2019.

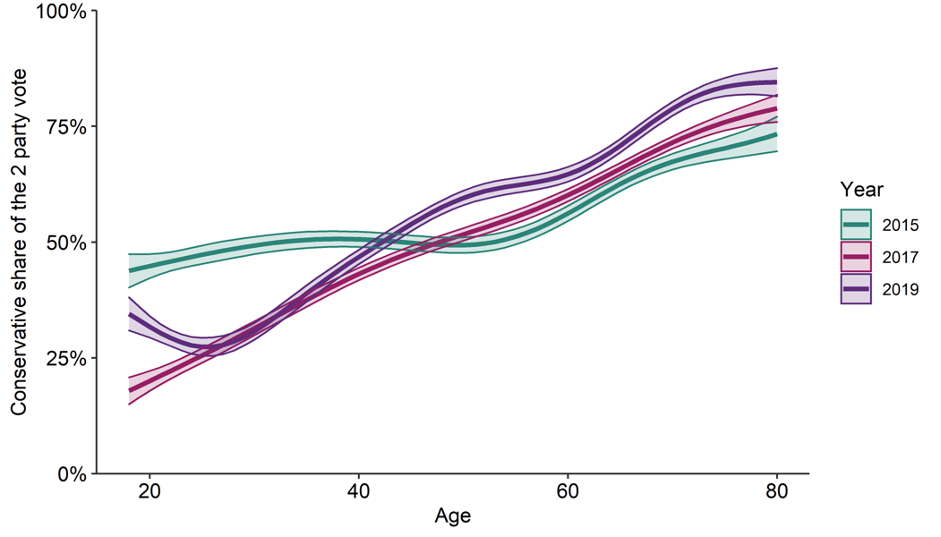

5. Age

Another increasingly important electoral cleavage which has been heightened by Brexit is age. While older voters have long been regarded as more conservative, the increasing importance of the cultural values dimension (especially immigration) and Brexit to vote choice has intensified the effect of age on vote choice, which is largely attributable to attitudes towards Europe and immigration. This is illustrated in Figure 4 which shows the relationship between age and the Conservative share of the two-party vote in 2015, 2017 and 2019. Age was already a strong predictor of Conservative voting in 2015, but this relationship greatly expanded in 2017 and remained similarly strong in 2019.

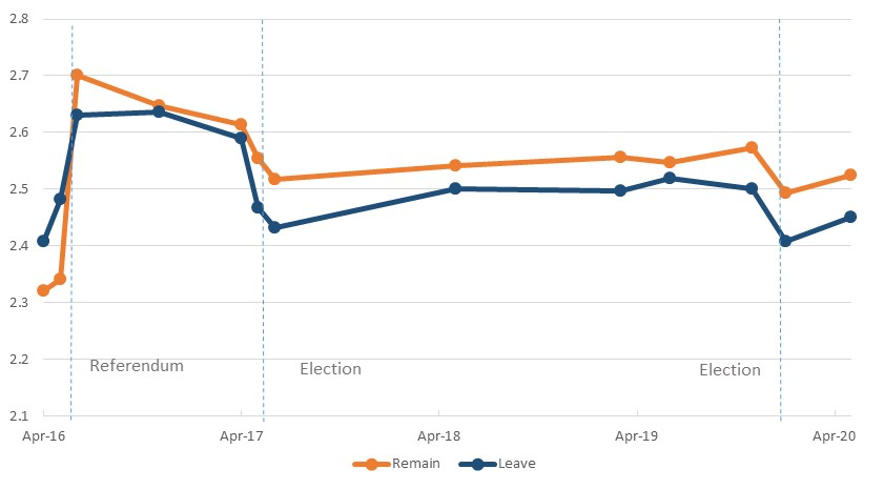

6. Brexit Identities

Underlying changes in party identification are normally expected to accompany realignment alongside changes in voting behaviour. However, a further symptom of realignment in an age of party dealignment may be the rise of competing social and political identities, filling the vacuum created by the decline of traditional party identification. Figure 5 shows how the strength of Leave and Remain identities grew in parallel in the period following the referendum in 2016, peaking in the period between the referendum and the 2017 General Election. Brexit identities receded only very slightly in 2019 despite the passage of another two years since the referendum and have recovered slightly since. Moreover, on average, both Remain and Leave identities were stronger than traditional party identifications in 2019.

The evidence presented here – of shifting electoral cleavages around social class, geography, education and age; the persistence of alternative political identities; and a reversal in electoral volatility–suggests that Brexit continued to structure electoral choices in 2019. While these developments are consistent with the early stages of a realignment, it is too early to determine whether they should be considered a long-term critical realignment. Whether the changes are really here to stay will depend partly on the whether ‘cultural’ issues like immigration and minority rights, which have divided voters over recent years, continue to divide them after Brexit. Should this be the case we might expect Brexit identities to evolve into more general social conservative/liberal identities. Alternatively, traditional economic issues may return to the fore as the after-effects of Brexit and COVID-19 expose political differences between the haves and the have nots. EU identities could evaporate and voters may again start to desert the major parties, leading to a return to high levels of electoral volatility. Which of these futures comes to pass remains to be seen. One clue lies in the fact that attitudes towards the COVID response seem to be determined more by traditional left-right economic values than by those liberal-authoritarian values which underpin the Brexit divide, and the Conservatives’ new voters in December 2019 are the first to judge the Conservative government’s handling of the coronavirus crisis more harshly, and shift to an undecided vote choice. Ultimately, however, the only certainty about the future of British electoral politics is that it will be driven by unforeseen events and, ultimately, to how political actors respond to those events.