Zack Grant, Jane Green, Geoffrey Evans

University of Oxford

The growing age gap in voting behaviour is one of the most important and striking trends in recent British elections. The old are increasingly Conservative; the young are increasingly Labour. Using newly released British Election Study (BES) data from May 2022, we show that, despite these patterns, the Conservatives are currently not seen to be looking after the interests of the retired any better than Labour. Surprisingly, retired voters enter the ongoing economic crisis feeling less well represented by either major party than any other social group.

In the 2019 general election, the Conservatives were ahead of Labour 59% to 20% among the over-65s. Among the under-30s, however, they trailed Labour 21% to 58% (BES 2019 figures). The Conservative dependence upon an older electorate – partly enabled by a large age gap in turnout – may have policy consequences. As we write, the government remains committed to increasing pensions with inflation (reinstating the triple lock), protecting retirees from some of the worst of the cost of living crisis, but has not committed to doing the same for working-age benefits. Older Britons are more likely to feel economically secure, and have benefited – relatively speaking – from the intensification of intergenerational wealth inequality in recent years. When you further factor in the better representation of the senior voters’ preferences on high-profile issues such as Brexit, the National Insurance tax rise to fund adult social care, and the increase in University tuition fees, you can see why claims of agerontocracy in British politics have gathered pace.

Despite these trends, do the public – and, more importantly, older voters themselves – feel that the old are better represented in politics?

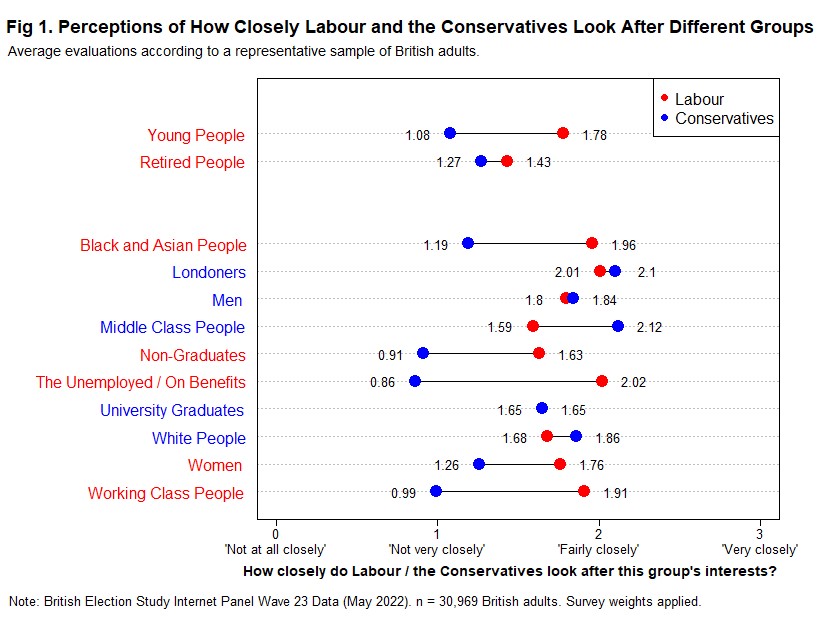

We asked BES respondents, in May 2022, how closely they thought the different political parties ‘look after the interests of’ different groups, on a scale of 0 to 3. Figure 1 shows the average score our respondents gave to Labour (red) and the Conservatives (blue) for each group. Surprisingly, while Labour is seen by far as a party that looks after the interests of ‘young people’, the Conservatives are not seen as better representing the interests of ‘the retired’, where Labour has a modest lead. In fact, the Conservatives are seen as only slightly better at representing the retired than the young, or other traditionally non-Conservative voting demographics, such as black and Asian people.

This presents something of a puzzle.

One explanation might be the question of what people are thinking of when they are thinking of ‘the retired’. Do people think of vulnerable, poorer people when they think of older generations? This would chime with the other data points in Figure 1, which suggest that BES respondents think the Labour Party looks after all kinds of disadvantaged groups better than the Conservatives, including the unemployed, the working class, and ethnic minorities.

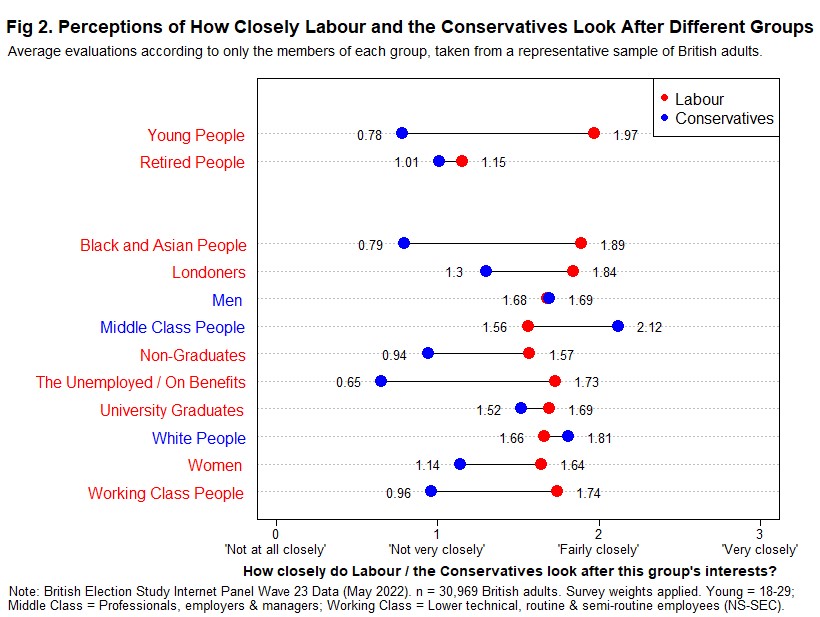

These trends become clearer still when we focus only on the evaluations of the parties by members of the particular groups in question (Figure 2). I.e. we look here at whether those who report being retired think the Conservatives or Labour look after their interests better. We compare that to the same comparison for young people (defined as the under-30s, in keeping with public perceptions of who counts as ‘young’), as well as all the other groups for comparison (e.g. women are asked about women’s representation etc.). Membership of most of these groups is intuitive, but note that we define ‘working’ and ‘middle class’ people as those with lower technical, routine or semi-routine jobs and professionals, managers and employers, respectively.

As one might expect given their strong electoral support for the party, the young overwhelmingly evaluate Labour as better placed to represent their interests. In fact, the young see a bigger gap between Labour and the Conservatives’ relative ability to look after their interests than any other social group, including minorities and the unemployed. In contrast, the greater (electoral) representation of older voters by the Conservatives has not led the retired to think the Conservatives look after their group better. In fact, the retired think that neither of the two largest parties looks after their interests particularly well. They appear to feel uniquely disenfranchised by the major British parties. All of the other types of respondent gave at least one major party over half marks (1.5/3), on average, for the representation of their group. This finding will be striking to any observer of British politics who sees the ‘boomer generation’ as particularly blessed with political attention.

One explanation for these findings might be that many older people don’t identify particularly strongly as a ‘retired’ person. They may feel quite well looked after by the Conservative government in their own views and circumstances, but not identify their interests with those of ‘the retired’ at large (again, possibly because, despite recent economic trends, this group was historically synonymous with deprivation).

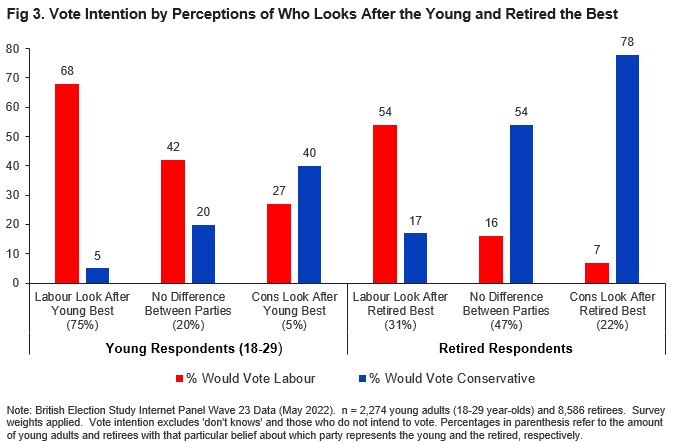

Still, could the Conservatives’ seemingly weak ‘pro-pensioner’ brand become an electoral risk to Sunak, and a potential asset for Starmer, at the next election? Alternatively, could the Conservatives start to poll better amongst under-30s if Labour’s ‘pro-youth’ brand were to erode slightly? Figure 3 explores these questions by comparing the vote intention of young and retired respondents who rated either Labour or the Conservatives as best at representing their age cohort (as well as those who gave both parties the same score).

There is a very strong relationship between thinking a party represents one’s age cohort better and supporting that party. For instance, a retired person who thinks the Conservatives best look after their group is 71 percentage points more likely to vote for that party than Labour. Labour are similarly dominant among under-30s who think that they best look after the youth. The potential problem for the Conservatives, however, is that while Labour can rely on 75% of young adults clearly identifying them as the party for the young, only 22% of retired respondents are similarly sure that the Conservatives best represent their own group. While still better than the mere 5% of under-30s who identify the Conservatives as best representing the young, this does suggest a potential asymmetry. While more retired people have been voting Conservative, they are not convinced that the party is clearly best placed to represent them as a group. In contrast, younger voters’ increased support for Labour is underwritten by a strong sense that the party does a decent job (in both relative and absolute terms) of looking after their interests.

Does this mean that the Conservative’s recent electoral lead among older voters is a fragile one? There are some reasons for scepticism. While slightly more retirees do see Labour as better placed to represent the retired, a near majority think that neither of the major parties have an advantage here. Furthermore, amongst this group the Conservatives still lead Labour by 38 percentage points. Clearly other issues that are not easily reducible to group interests – such as perceptions of crime, healthcare, and competent management of Britain’s economy – are also playing a big role in driving people’s vote choice. Other researchalso suggests that voters are, in general, less likely to switch parties once they have remained in the electorate for a longer period of time. It could be that the habit of voting Conservative outlasts perceptions that this party truly has a strong edge in representing the narrow interests of a social group that one may not even feel particularly attached to in the first place.

However, we can say that the Conservatives have clearly entered the current difficult climate without a strong party brand as the party for the retired to compensate for any further potential erosion of their previous lead over Labour on the ‘fundamentals’ such as party leader likeability or handling Britain’s economy. Whether they can strengthen this brand – or, alternatively, close Labour’s own lead in looking after the young – remains to be seen.

The findings here beg the question as to whether any party – Labour or the Conservatives – could ever reap big electoral rewards by being seen to represent both the young and the retired. Is an intergenerational electoral coalition possible? What sort of policies would be needed to forge one? This project is part of an ongoing, British Academy-funded research project by the present authors, in collaboration with the Resolution Foundation. For more information on our project, which shall be presenting findings in spring 2023, please see our website, and follow @ZackG_Politics and @ProfJaneGreen on Twitter for updates.